For this first leg of the documentary, Uluru was the focal point, and it’s why so many posts over the past few weeks have been devoted to it. Uluru is such a looming presence in Australia that it requires a significant amount of time to dwell on it. For me, writing as a visually impaired filmmaker, it’s been front and center in my mind since I first came up with the concept for The Palette Project – exploring the world, one color at a time – last May. As the virtual heart of the Red Centre, it is the natural fit for the color Red.

I’ve also written about how this landmark has been in my mind for much longer than just the past year. I first read about Uluru – referred to at the time as Ayers Rock – in my college days. It’s taken me a lot longer to get here than I would have liked, and I can report with some degree of authority that a dream deferred is indeed a dream denied. I think anyone who writes… even casually… about travel will agree with the sentiment that just because a destination isn’t going anywhere, it hardly means you should go nowhere. Get out, experience our world. Do this.

I use Uluru as an example because this is a place that should be in your mind, but here’s the rub: you have to want it there. Even when you’re there, you have to really want to be enmeshed in what Uluru is all about. For me, as a person who needs to sense The Rock as much as see it, this is important, but it should be important for everyone. There’s a certain amount of… let’s call it Disneyfication… going on at Uluru. Parks Australia has worked very hard and in concert with the Anangu Aboriginal owners to make Uluru-Kata Tjuta accessible and enjoyable, but you have to be prepared for what Uluru is… and what it decidedly is not.

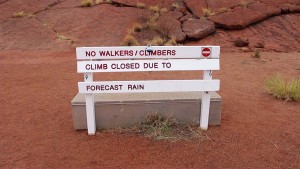

Uluru is not Everest. It’s not Denali. It’s not an adventure challenge to be checked off a list. In the time we were on the ground, we ran into more adventure travelers then we could count, and most of them were disappointed, because there is just not much of a physical challenge to Uluru for most people. Parks Australia does go to quite reasonable lengths on the Uluru-Kata Tjuta website

to point this out. Almost all of the trails are of a moderate grade. Many of them are at least in part accessible to physically impaired individuals. Your biggest challenge will be the extreme heat of the outback, and this is not an issue to be taken lightly. With temperatures well over 90 degrees Fahrenheit and often over 110 degrees for most of the year, it’s a place where three to four liters of water per person is a good starting point (we each carried six liters). It’s a feast for the senses, but if you’re looking for your next K2, you will be sorely disappointed, as were many of the backpackers, trail bikers and climbers we met. I’m sorry to report this, but one of the most common phrases you’ll hear at Uluru is “this is it?”

And that’s why we need to talk about climbing Uluru.

To me, this is what happens when you try to shoehorn your expectations into a reality that has its own agenda, and I think it’s why so many people still want to climb Uluru… despite the fact that everyone with even the slightest amount of ownership or investment in the place would prefer you don’t. My cinematographer and I went back and forth on this very issue for months, and we didn’t make our final decision until the days just before our arrival. The final decision was we were not going to climb Uluru. I maintain a belief that if you want to do something badly enough, you’ll find a way to rationalize doing it, even if it’s the wrong thing to do… but that rationalizing a decision is the worst way to decide to do something.

As we spoke with other travelers, it was plainly obvious there was a lot of rationalizing going on. The reasons boiled down to three arguments:

- We traveled all this way so we deserve to make the climb.

- There’s nothing else to do here but make the climb.

- We just really, really want to.

In the end, we couldn’t justify a climb with any of those rationalizations. The fact of the matter is,simple respect required us to abide by the wishes of our Anangu hosts. They’ve been here longer, and they understand this place in a way that I, as yet, cannot. Climbers on Uluru, to the Anangu, are human pollution, and the effect those climbers have on the environment… in the form of runoff, waste and wear… is severe. As an aside, the Anangu refer to climbers as minga, the word for ants. Footsteps on The Rock often don’t dissipate for days or even weeks. This should tell us something about how fragile the landscape is. Even to film at Uluru-Kata Tjuta, we had to sign releases promising we would under no circumstances go off-trail. This was hardly a sacrifice.

Yet, so much of Uluru is hidden in plain sight. It’s easy to be deceived by the well groomed trails, the burger and sushi bars at nearby Yulara, and the immaculate two tier wooden platforms at the sunrise viewing area with the massive car lot and boardwalk paths. You begin to feel you’re missing something. Easy hikes, no campsites and hotels as well appointed as anything you’ll fid in Orlando. This is the outback?

Well, yes it is, but you have to want it. My advice is to approach Uluru with the same measured nature that the Anangu have practiced for thousands of years. Don’t treat the 10K trail around the base as a speed test. Linger in the silence of the watering holes. Treat the sacred art on the rock faces as a gift that rewards your presence, not as a trophy for your Instagram feed that proves you were there. This matters.

And do what I did. Feel Uluru. I mean this quite literally. I’ve lived in Colorado along the Front Range of the Rockies, and the one truism about mountains is that there is no distinct point where you can say “this is where the mountain starts.” That’s kind of the magic. The mountain just… becomes itself.

Not so with Uluru, and this is a different kind of magic. What’s amazing about Uluru is that you can literally put your hand on the exact point where the monolith rises out of the desert. I’ve done this, and I can tell you that there is no need to climb Uluru once you’ve felt it from the bottom up. It’s an epiphany – that Uluru is going to feel like this no matter where you are on it.

I came to Australia in search of the color Red. I came as a visually impaired storyteller, because I had to know if there was a way to experience color beyond sight. The answer is yes, this is possible. Red is power, solidity and accomplishment.

And at Uluru, it’s also respect.

What are your thoughts about climbing Uluru? Post below.